Well over a decade ago, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit tossed aside a case I filed as a young, pro se litigant, without oral arguments, on the basis that TSA screeners aren’t “officers of the United States” and therefore can’t be sued under laws that hold such officers accountable. This decision, along with the sting of being denied justice over a brief false arrest by TSA, was one of the most motivating factors for enrolling in law school, which I did months later.

Until this week, I had obtained rulings in 3 other Courts of Appeals holding that TSA screeners are “officers of the United States” who may be sued under this particular law (and two other law firms obtained similar rulings in another pair of appeals courts), but that pesky contra opinion from the Eleventh still remained. On Wednesday, however, my firm obtained victory in Koletas v. United States, 24-10505 (11th Cir. 2025), reversing U.S. District Judge Sheri Polster Chappell in the Middle District of Florida:

As our sister circuits noted, the reasoning in Corbett I is not persuasive for two reasons. First, it did not conduct a textual analysis of the relevant statute, the FTCA. See e.g., Iverson, 973 F.3d at 850 (explaining that the ATSA postdates the FTCA and cannot “silently alter[]” the scope of a statute enacted 30 years prior). Second, as the Third Circuit explained, it is perfectly consistent for TSOs to be classified as both “employees” and “officers,” but not “law enforcement officers.” See Pellegrino, 937 F.3d at 171 (“[T]here is no textual indication that only a specialized ‘law enforcement officer’ in the [ATSA] qualifies as an ‘officer of the United States’ under the [FTCA].”).

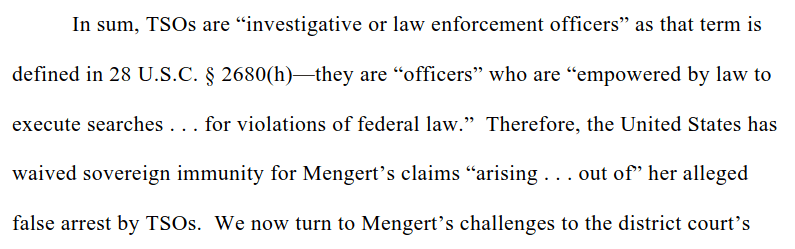

Because the government does not meaningfully defend Corbett I’s holding that TSOs are not “officers” under the law enforcement proviso, and because we are persuaded by the plain-meaning analysis conducted by our sister circuits, we conclude that TSOs qualify as “officers” under the proviso.

Notable of the lower court’s ruling was that the prior decision in my long-ago case was not binding precedent because it was an “unpublished” decision of the Eleventh Circuit, and the lower court not only adopted it wholesale, it completely ignored (as in, did not even mention) the other then-four appellate courts to go the other way:

But the district court’s economical dismissal order did not grapple at all with the thorough analyses provided by the Third and Eighth Circuits in the cases cited by Koletas, nor with other then-recently published decisions from the Fourth and Ninth Circuits reaching the same conclusion.

…

Accordingly, we caution district courts from relying on our unpublished decisions purely because they are our decisions, without carefully evaluating the legal suasion of an unpublished Eleventh Circuit opinion.

It is, of course, too late to go back and re-open my case, but my client here will now have her day in court after having been unlawfully strip searched by TSA screeners in Orlando — a massive win for justice.

The issue of whether TSA screeners may be sued for intentional torts under the Federal Tort Claims Act is now 6-0 in favor of “indeed they may!” in the twelve circuit courts (and, now that the government has lost the one opinion in its favor, I expect this may be the end of the issue). Summary of the law by circui

- First Circuit – No Decision

- Second Circuit – No Decision

- Third Circuit – TSA Lost (Pellegrino, 2019)

- Fourth Circuit – TSA Lost (Osmon, 2023)

- Fifth Circuit – No Decision

- Sixth Circuit – No Decision

- Seventh Circuit – No Decision

- Eighth Circuit – TSA Lost (Iverson, 2020)

- Ninth Circuit – TSA Lost (Leuthauser, 2023)

- Tenth Circuit – TSA Lost (Mengert, 2024)

- Eleventh Circuit – TSA Lost (Koletas, 2025)

- DC Circuit – No Decision

In 2012, a TSA screener refused to allow me to leave a checkpoint after I told him I wouldn’t consent to having him touch my genitals. He

In 2012, a TSA screener refused to allow me to leave a checkpoint after I told him I wouldn’t consent to having him touch my genitals. He  On April 20th, 2022,

On April 20th, 2022,