TSA loves arguing that it’s exempt from Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA) lawsuits based on the misconduct of its checkpoint screeners. The text of the FTCA states that it only applies to intentional misconduct when committed by an “officer of the United States who is empowered by law to execute searches, to seize evidence, or to make arrests for violations of Federal law,” and TSA argues that checkpoint screening isn’t really “executing searches.” Given that the FTCA is the only viable way to redress checkpoint abuse in the courts, it’s no wonder that they give serious effort to this strategy despite it requiring… er, linguistical creativity… to say that TSA screeners don’t search.

Every U.S. Court of Appeals to hear the matter and come up with a precedential ruling — four so far — has ruled against them. I argued two of them that were decided last year (Osmon in the Fourth Circuit, Leuthauser in the Ninth) and the Third and Eighth Circuits took the same path in 2019 and 2020, respectively. But, there are twelve federal circuits that hear general appeals and a decision of one of them is only binding within the states covered by that particular circuit, so unless the Supreme Court takes up the matter, TSA is free to give all twelve circuits a try. If TSA wins in one of them, it can use that as a reason to persuade the Supreme Court to hear the case (lawyers call this a “circuit split”).

So try they do. In March, I’ll be doing oral arguments in Mengert v. U.S., on behalf of a woman who was subject to a back-room strip search by TSA screeners (TSA rules categorically prohibit their screeners from conducting strip searches for any reason). TSA lost on the FTCA issue in the lower court and is now raising it in the Tenth Circuit. TSA also tried again in a Florida federal district court in Koletas v. U.S., and prevailed on the FTCA issue in that trial court. That Florida ruling rubber-stamped TSA’s argument without even mentioning the Third, Fourth, Eighth, and Ninth circuit rulings, which is pretty outrageous even for Florida. We filed a notice of appeal to the Eleventh Circuit.

So in summary:

- First Circuit – No Decision

- Second Circuit – No Decision

- Third Circuit – TSA Lost (Pellegrino, 2019)

- Fourth Circuit – TSA Lost (Osmon, 2023)

- Fifth Circuit – No Decision

- Sixth Circuit – No Decision

- Seventh Circuit – No Decision

- Eighth Circuit – TSA Lost (Iverson, 2020)

- Ninth Circuit – TSA Lost (Leuthauser, 2023)

- Tenth Circuit – Oral Arguments in March 2024 (Mengert)

- Eleventh Circuit – Oral Arguments Likely Winter 2024 (Koletas)

- DC Circuit – No Decision

In 2012, a TSA screener refused to allow me to leave a checkpoint after I told him I wouldn’t consent to having him touch my genitals. He

In 2012, a TSA screener refused to allow me to leave a checkpoint after I told him I wouldn’t consent to having him touch my genitals. He

On April 20th, 2022,

On April 20th, 2022,

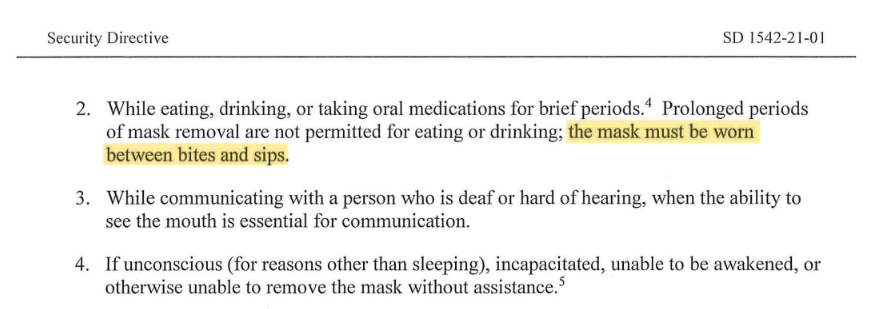

It seems that masks reduce transmission of coronavirus: some studies showing reduction of

It seems that masks reduce transmission of coronavirus: some studies showing reduction of