Many people don’t like the idea of having their home address so easily searchable on the Internet. It used to be that if you wanted a way to receive mail without giving up where you live, you got a post office box, which is ok but let’s face it, there’s not much worse in this world than having to go to the post office.

I love to travel (hence the origins of this blog), and for me, I also would like to be able to receive my mail even when I’m not home. Rather than burdening my friends, I use one of the many services out there that receive mail on your behalf and, at your request, scan your mail and e-mail it to you, forward your mail to you, or simply drop it in the shredder if you don’t want it.

The services range in price from about $20 for the basics, and it’s the easiest way to get your address off the Google while still maintaining communication with those who still find it necessary to send paper. Two that I’ve used that I’ve been happy with (and receive no commission from) are:

- Earth Class Mail (more expensive but choice of address in a bunch of major cities)

- Mailbox Forwarding (less expensive but choice of address in only 3 cities)

One cool tip: with the check deposit feature that most banks have in their mobile apps, if you receive a check, you don’t have to request it be forwarded to deposit. Just request that they scan the item and then either print and endorse, or if you’re extra fancy, you can endorse using any graphics program and use the app to take a picture of your screen. It actually works.

This is one of a 30-part series, “No Surveillance State Month,” where daily for the month of June I’ll be posting ways to avoid invasion of your privacy in the digital age. The intent of these posts is not to enable one to escape detection while engaging in criminal activity — there’s still the old-fashioned “send a detective to watch you” for which these posts will not help. Rather, this series will help you to opt-out of the en masse collection of data by the government and large corporations that places Americans in databases without their knowing and freely-given consent for indefinite time periods. We all have the right to privacy, and I hope you demand it.

In the computer security world, “social engineering” is the process of persuading a person to give up a password or other important piece of data by tricking them. Typically done either by e-mail (or other electronic message, like Facebook) or phone, the person on the other end will pretend to be your IT help desk, your bank, some kind of investigator, or other person with whom you may trust the data. (When done by e-mail, this is more specifically known as “phishing.”)

In the computer security world, “social engineering” is the process of persuading a person to give up a password or other important piece of data by tricking them. Typically done either by e-mail (or other electronic message, like Facebook) or phone, the person on the other end will pretend to be your IT help desk, your bank, some kind of investigator, or other person with whom you may trust the data. (When done by e-mail, this is more specifically known as “phishing.”) When Facebook was released, I was a college student at one of the dozen or so universities first given access to Facebook. I was probably somewhere around the 50,000th user of the now 100,000,000, and I’ve watched it evole from a PHP script where you could find the cute girl down the hall knowing only her first name (and read her whole profile without even being friends!) to a massive corporation that connects nearly every young person in the western world.

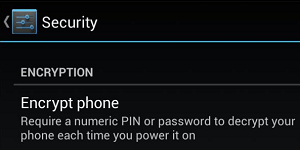

When Facebook was released, I was a college student at one of the dozen or so universities first given access to Facebook. I was probably somewhere around the 50,000th user of the now 100,000,000, and I’ve watched it evole from a PHP script where you could find the cute girl down the hall knowing only her first name (and read her whole profile without even being friends!) to a massive corporation that connects nearly every young person in the western world. Not all phones can do this, but most Android phones can. By now, you know that encryption is the process of locking data with a key such that (when done right) even serious adversaries cannot unlock it. You can encrypt data for transit (such as when you view a Web site over HTTPS), and you can encrypt data for storage. The latter protects your data in the event your device is stolen (or “seized”).

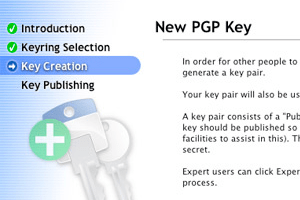

Not all phones can do this, but most Android phones can. By now, you know that encryption is the process of locking data with a key such that (when done right) even serious adversaries cannot unlock it. You can encrypt data for transit (such as when you view a Web site over HTTPS), and you can encrypt data for storage. The latter protects your data in the event your device is stolen (or “seized”). We’re now half way through the No Surveillance State Month, and what a busy month it’s been! Part 15 discusses an important yet technically difficult topic: encrypting your e-mails as they are in-transit.

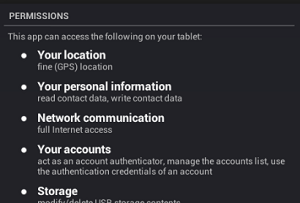

We’re now half way through the No Surveillance State Month, and what a busy month it’s been! Part 15 discusses an important yet technically difficult topic: encrypting your e-mails as they are in-transit. As “apps” become more and more ubiquitous on all our devices, it becomes all that much more important to keep track of what your apps are doing. If you use an iPhone or an Android device, every time you install an app, you get a warning like the one pictured here.

As “apps” become more and more ubiquitous on all our devices, it becomes all that much more important to keep track of what your apps are doing. If you use an iPhone or an Android device, every time you install an app, you get a warning like the one pictured here. Another pretty simple one for you. If you surf the Web, but never update your operating system, Web browser, and plug-ins (especially Flash and Java), you’re asking for it. Every few weeks, another “exploit” is published — exploit being a fancy term for “way to take over your computer.” Software manufacturers (generally) work very hard at putting out “patches” — software to fix the software and make the exploit no more.

Another pretty simple one for you. If you surf the Web, but never update your operating system, Web browser, and plug-ins (especially Flash and Java), you’re asking for it. Every few weeks, another “exploit” is published — exploit being a fancy term for “way to take over your computer.” Software manufacturers (generally) work very hard at putting out “patches” — software to fix the software and make the exploit no more. Today’s tip is an easy one. When you’re browsing the Web, if the address of the page you’re viewing starts with “http://”, you’re viewing a non-encrypted Web page, which means that it’s possible someone can intercept what you’re doing (a neighbor listening in on your WiFi, the NSA, etc.). On the other hand, if the address starts with “https://”, it is encrypted using “SSL” and likely safe. The “s” means secure!

Today’s tip is an easy one. When you’re browsing the Web, if the address of the page you’re viewing starts with “http://”, you’re viewing a non-encrypted Web page, which means that it’s possible someone can intercept what you’re doing (a neighbor listening in on your WiFi, the NSA, etc.). On the other hand, if the address starts with “https://”, it is encrypted using “SSL” and likely safe. The “s” means secure! Yesterday I

Yesterday I